Military aviation expert Tom Cooper continues to analyze the war in the sky and on the battlefield between Ukraine and Russia. How does the Air Defense system function? Presented here is the second part of the analysis of the aerial warfare.

To continue the story of how are Ukrainians deploying their Storm Shadows (and 15 SCALP-EG missiles supplied by France…. Hope, this didn’t prove too hard or too much for Mr. Macron and pooh li’l France….), and as next, let’s have a look at the Russian air defences.

Generally, people think about warfare in terms of medieval jousting tournaments. Like: ‘Storm Shadow vs Pantsyr’. As if the Pantsyr would be the only weapon system a Storm Shadow has to overcome in order to hit its target…

In reality, things just couldn’t be any different from that: instead, every single Storm Shadow - and every single round fired by an Ukrainian-operated M142 HIMARS or M270 MLRS - has to overcome an entire integrated air defence system (IADS) consisting of (at least):

- S-400 Triumpf (SA-21 Growler) long-range surface-to-air missiles (SAMs)

- Buk M2/M3 (SA-17 Grizzly) medium-range SAMs

- Tor M2 (SA-15 Gauntlet) short-range SAMs, and

- Pantsyr S1/S2 (SA-22 Greyhound) close-in weapons system including SAMs and two 30mm autocannon.

….and that in addition to a host of early warning/surveillance- and fire-control radars, supported by systems for electronic warfare (including plentiful of GPS-jammers, just for example).

When all of this is put together, the question is: what is that looking like? How to ‘visualise’ all of this….?

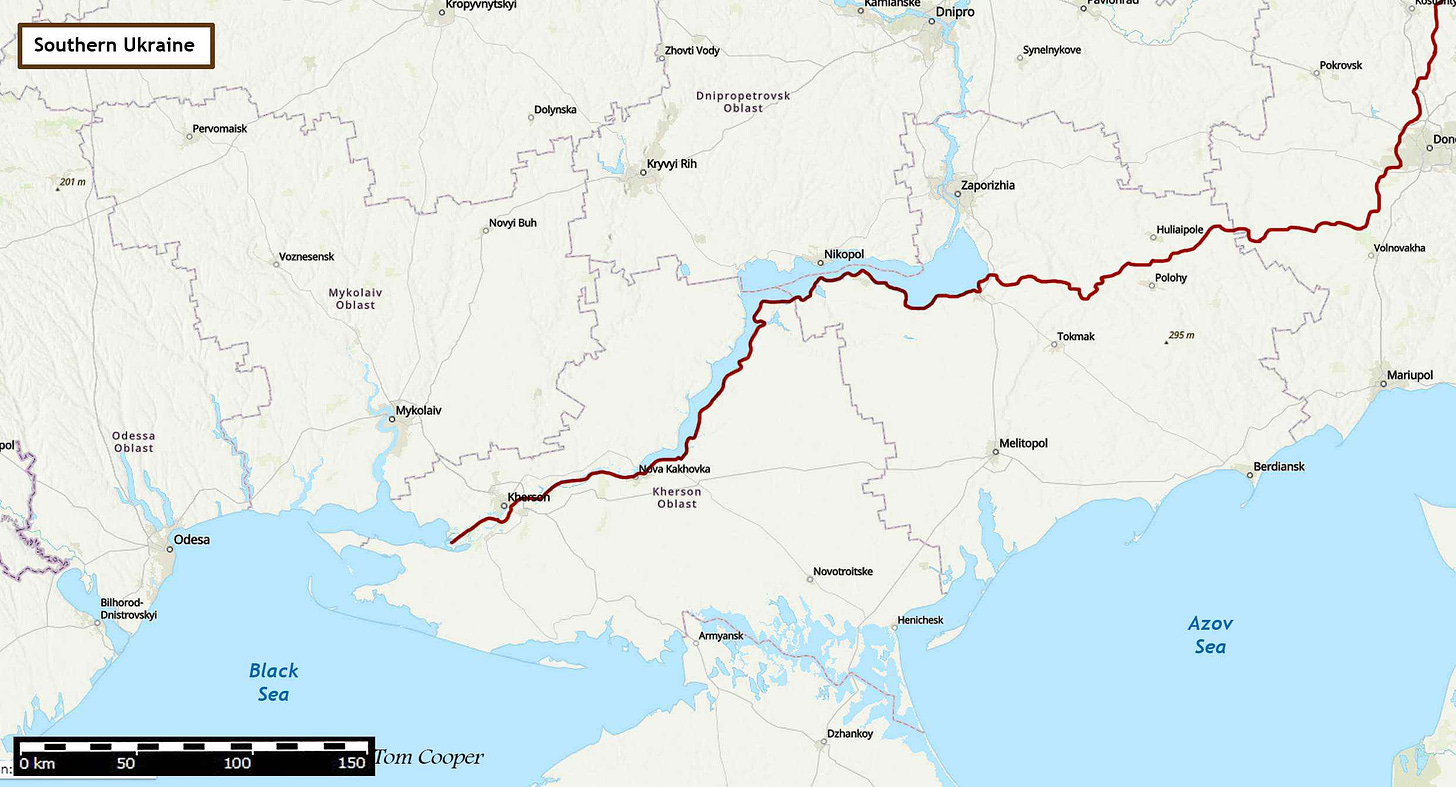

From the mainstream- and the social media, we’re used to ‘frontlines’-maps, something like this:

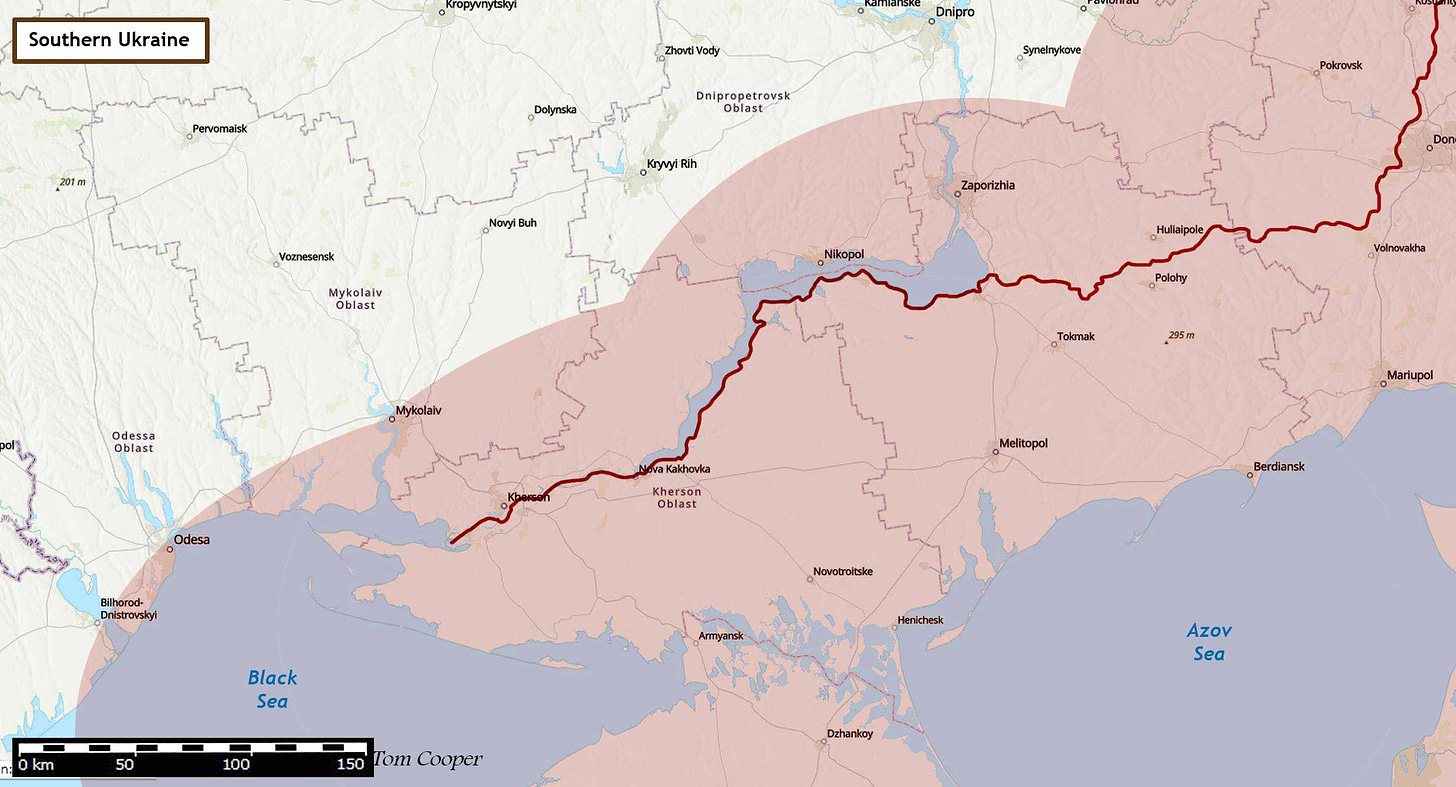

Oversimplified, and when it comes to the pilots and weapons system officers (WSOs) of the Ukrainian Air Force (PSU), well, for them the situation is actually looking at least like this:

….with the red-shaded areas denoting the airspace within reach of longest-ranged SAM-systems operated by the Russians: such like S-400, for example.

Now mind: alone this - one - weapons system is a ‘beast’. The S-400 has not only a huge range (nominally: over 350km), but some of its missiles have active radar homing in their terminal flight phase, and that nifty ‘dive on target’ capability. Combined, this means: they can track their targets on their own and have an ‘over-the-horizon’ engagement capability. Little surprise then, back in March of the last year, a Russian S-400 operated in southern Belarus claimed an Ukrainian jet shot down over a range of more than 110km….

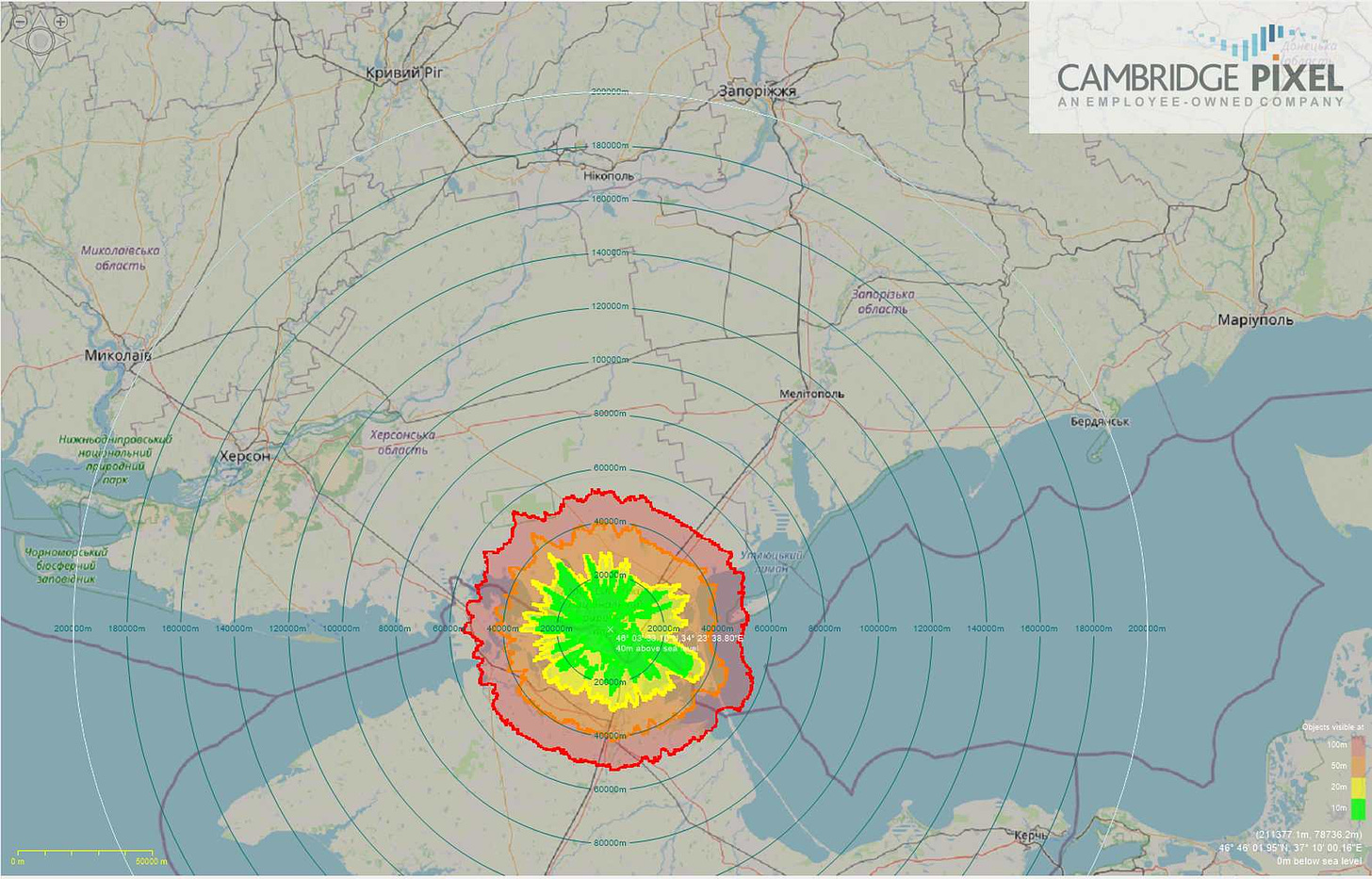

Moreover, S-400s are usually supported by mast-mounted-antennas, which are significantly improving their detection- and tracking capabilities, especially against low-flying target. The standard mast antenna for S-400 is the 40V6MR (ASCC/NATO is calling that system the ‘Clam Shell’), which is some 24m tall. But, the system can be coupled with the slightly older, yet taller, 40V6MD (also ‘Clam Shell’) antenna, which has a mast of 38.8m. That’s looking something like this:

To demonstrate just how much a 40V6 can see from, say, a position ‘somewhere in the Chongar area’, have set the following example, with a radar atop its 38.8m mast, range of 200km, and colours denoting:

- Green: altitude of up to 10m

- Yellow: altitude of up to 20m

- Orange: altitude of up to 50mm

- Red: altitude of up to 100m

Means: anything flying above 100m outside the red line and out to a range of about 200km – is detectable by that radar. This also means: when approaching that radar (and thus the S-400 SAM-site), only objects flying at less than 10m are going to remain undetected – at least until reaching a distance of about 20,000m/20km: then this radar has a good chance of detecting them, too.

And mind: that’s just one type of radars used by the Russians. They also have over-the-horizont radars (OTHs), which can see ‘all the way to Germany’, literally. Arguably, they’re not very precise, but: they can at least seriously indicate aircraft movements 2,000 km away. Then other systems are taking over the job of tracking at shorter ranges…

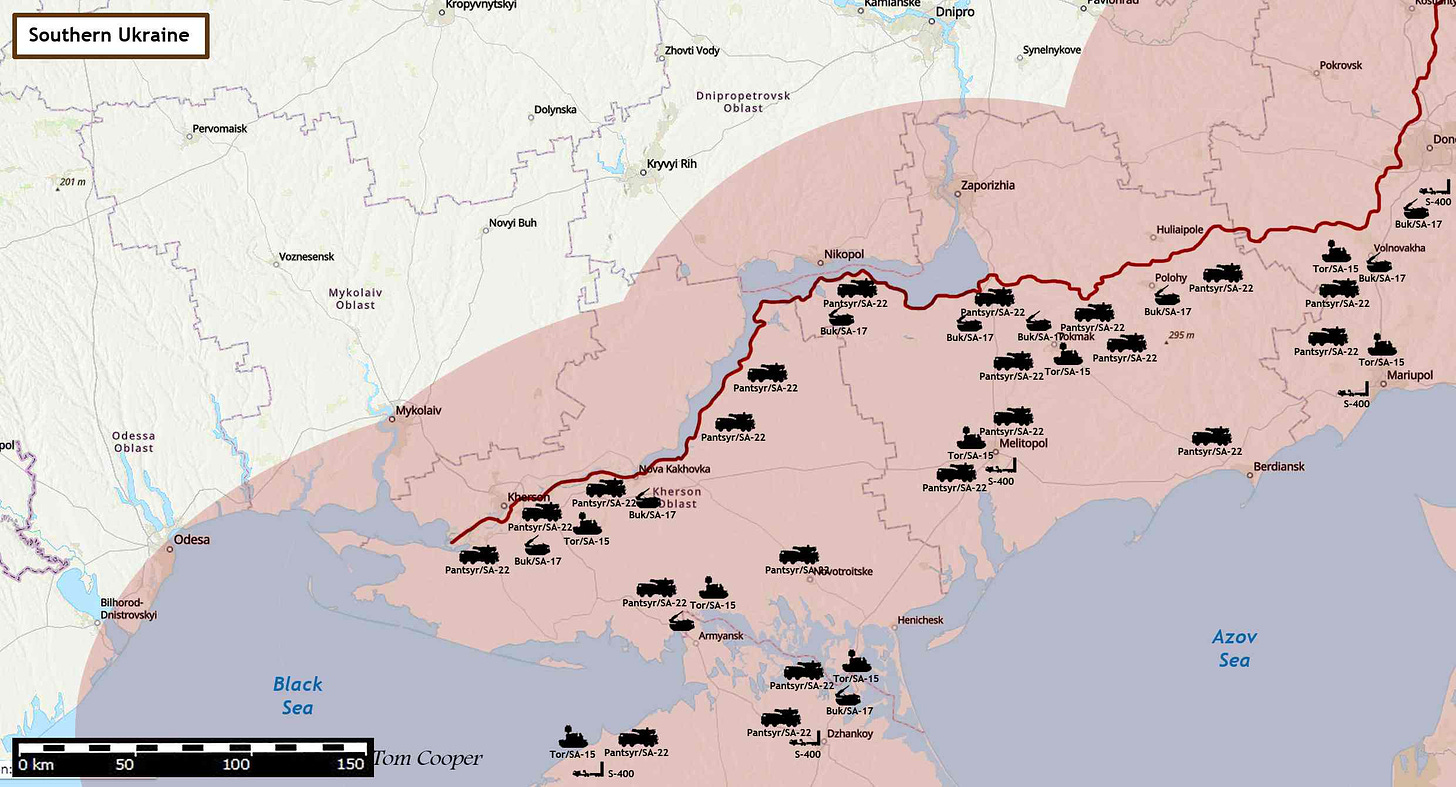

Weapons-wise, one then has to add Buks – which also have their own mast-mounted early warning/surveillance radars – Tors and Pantsyrs, at least. This is resulting in the actual situation looking ‘at least’ like this (where I’m sure I’ve ‘undercounted’ available Russian SAM-battalions in southern Ukraine by a wide margin, principally for reasons of space and clarity):

At least in theory, this means that nothing flying at altitudes above 10m over Ukraine remains undetected for very long – and: the closer it gets to the ‘frontlines’, the more dangerous things are getting.

But, that’s still not all the threats PSU-fliers are facing…

Indeed: because the Russians are not only using their ground-based air defences (GBADs), but also interceptors armed with R-37M long-range air-to-air missiles - like MiG-31s and Su-35s - the actual situation is looking something like this:

To make things ‘even more complex’, mind that the Russian units operating ‘lighter’ systems – Buks, Tors, Pantsyrs etc. – are regularly changing their position. Only their S-300-, S-350-, and S-400-systems can operate from such ranges that they are safe from anti-radar missiles like AGM-88 HARM, and thus they’re usually in the same position for weeks, months, even years. With other words: even if slightly changing its composition and positions - ‘every morning’ for example – the Russian IADS is a constant-, yet also ‘constantly changing’, ‘constantly adapting’ threat. All the time.

This is why both NATO’s electronic reconnaissance (or ‘intelligence gathering’) and the Ukrainian electronic reconnaissance are so important: this is why NATO is frequently sending its aircraft and UAVs like Boeing RC-135, Boeing P-8, Northrop Grumman RQ-4 Global Hawk, etc. – close to Russia: to ‘snif’ for enemy air defence systems, to track their work, and thus ‘fix’ their areas of deployment, their composition, their working frequencies etc. Their work is of crucial importance: at least for the crews of Ukranian helicopters, MiG-29s, Su-24s, Su-25s, and Su-27s - it’s results are a matter of life or death.

….which in turn is the reason why the Russians are lately trying to counter such aircraft and UAVs by attempting to ‘drive them away’: flying dangerous manoeuvres in their proximity, sometimes even dumping fuel or releasing flares in front of them…

Another result of the power of the Russian IADS is that aircraft and helicopters of the PSU are rarely flying at altitudes higher than 10-20m - at least whenever within 150km of the frontline. Just to avoid detection by the Russians and a possible attack by their interceptors or S-400s.

….and now mind: that’s still not all, or the PSU’s ‘sole problem’ in this regards.

As described back in May, the PSU has its own IADS. Thus, imagine one of my maps above, and then add similar ‘blue circles’ denoting positions of air defence systems operated by ZSU’s ground units – and you’ve ‘got the picture’. Ukrainian air defence systems might be not as numerous as those of the Russians. Indeed, many are concentrated around major urban centres ‘in the rear’, BUT: make no mistake, there are at least as many deployed along the frontline. Otherwise the VKS would be entirely free to operate over the frontline – which it is not.

All together this means: just in order to reach the frontline, PSU’s jets (and helicopters) have to pass one (own) IADS, in order to face another IADS (the Russian).

….and then make no mistake by thinking that because of the availability of very advanced systems for ‘identification friend-or-foe’ (IFF), the threat of being shot down by own air defences is non-existing. On the contrary, at war, and in air warfare - where decisions are always taken on basis of insufficient information, but within very short periods of time - it is extremely high: whether due to communication problems, enemy countermeasures, or an entire host of possible mistakes, the IFF is rarely working perfectly.

Quite a number of Ukrainian jets and helicopters was already shot down by own forces (just like an even higher number of Russian jets and helicopters was shot down by the Russian air defences). This is why many of PSU’s aircraft and helicopters are nowadays wearing prominent ‘means of quick visual identification’: that’s something like ‘last ditch attempt’ to show, ‘we’re friendly’ – at least to those troops that might try to shoot at them by shorter-ranged weapons, like MANPADS, machine guns, rifles etc. That’s why many of them have their entire undersides painted in yellow, like this one:

(….to be continued….)